Niels Bohr talked about Buddhism, Taoism (founded by Lao Tse) and psychology and their role in quantum physics:

"For a parallel to the lesson of atomic theory regarding the limited applicability of such customary idealizations, we must in fact turn to quite other branches of science, such as psychology, or even to that kind of epistemological problems with which already thinkers like Buddha and Lao Tse have been confronted, when trying to harmonize our position as spectators and actors in the great drama of existence."

Bohr used the so-called "wave-particle duality" -- to which Einstein and other notable physicists like Dirac where opposed and Einstein went so far as to call it "Bohr-Heisenberg religion" -- to turn a mathematical inequality known as the uncertainty principle into a philosophical statement known as the complementarity principle, presumably to reconcile physics and Eastern theosophy.

The principle states that a subatomic particle (the object) has a dual nature -- it could be localized and be a particle, or it could spread and act like a wave -- and the two realities are mutually exclusive. It is the experimenter (the subject) who decides which reality to be attributed to the quantum entity. Therefore, complementarity principle entangles the subject and the object, the epitome of Buddhism and Hinduism.

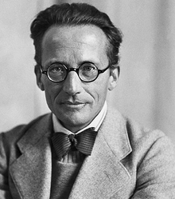

Werner Heisenberg was most influential in injecting Eastern theosophy in quantum physics. In his 1929 journey to the Far East, he had a long conversation with the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore about science and Indian philosophy. He revealed that,

After these conversations with Tagore, some of the ideas that had seemed so crazy suddenly made much more sense. That was a great help for me.

And in Japan, he delivered a lecture in which he said:

The great scientific contribution in theoretical physics that has come from Japan since the last war may be an indication for a certain relationship between philosophical ideas in the tradition of the Far East and the philosophical substance of quantum physics.

The statement above is a prime example of confirmation bias that plagues not only mysticism but sloppy scholarly research. The beliefs or "philosophical ideas" of scientists have no bearing on their science, as Heisenberg contends. We certainly do not conclude that Newton's discovery of gravity was "an indication for a certain relationship between" his belief that the earth was created 6000 years ago and his thought on gravity. Paul Dirac, who unified special relativity and quantum physics and consequently gave us anti-matter and founded the theoretical basis of the Standard Model and cosmology, was an atheist and detested mixing theosophy (of any kind) with physics. Should we conclude that his atheism prompted relativistic quantum mechanics?

Wolfgang Pauli believed that the separation of faith and knowledge would end in disaster. He argued that although at the dawn of religion all the knowledge of a particular community fitted into a spiritual framework, the advancement of society introduced knowledge that was in contrast to the old spiritual forms.

Pauli saw this as a threat to the ethics and values of the society and found the solution in a spiritual framework where faith and knowledge, science and religion, object and subject are unified. He expressed hope in quantum physics:

[the] very appearance of [Bohr's complementarity principle] in the exact sciences has constituted a decisive change: the idea of material objects that are completely independent of the manner in which we observe them proved to be nothing but an abstract extrapolation. ... In Asiatic philosophy and Eastern religions we find the complementary idea of a pure subject of knowledge, one that confronts no object.

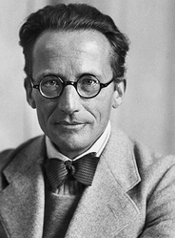

Erwin Schrödinger narrates his admiration of the Eastern theosophy in his biographical sketches, where he recalls that when the Emperor Karl abdicated and Austria became a republic, his life was affected by the breaking up of the Empire. Schrödinger had accepted a post as a lecturer in theoretical physics in Czernowitz and had already planned to spend all his free time acquiring a deeper knowledge of philosophy, having just discovered Schopenhauer, who introduced him to the Unified Theory of Upanishads.

Schrödinger recognizes the paradox of individuals having different minds while there is only one world, and finds the resolution of the paradox:

There is obviously only one alternative, namely the unification of minds or consciousnesses. Their multiplicity is only apparent, in truth, there is only one mind. This is the doctrine of the Upanishads. And not only of the Upanishads. The mystically experienced union with God regularly entails this attitude unless it is opposed by strong existing prejudices; and this means that it is less easily accepted in the West than in the East.

Eugene Wigner wrote a paper in 1939 in which he proved mathematically that a quantum particle has two important properties, namely mass and spin both of which could be zero -- yes, photon, the particle of light, is a real material particle even though it has zero mass. He won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1963 for this discovery.

Wigner, like his West European contemporaries who discovered quantum physics, had a keen interest in philosophy, especially as it related to quantum mechanics. In the 1960s, he proposed that the consciousness of an observer is the demarcation line which precipitates the collapse of the wave function. The non-physical mind is postulated to be the only true measurement apparatus. In short

through the creation of quantum mechanics, the concept of consciousness came to the fore again: it was not possible to formulate the laws of quantum mechanics in a fully consistent way without reference to the consciousness.

Hermann Weyl, the great German mathematician was also an influential figure in theoretical physics. He was instrumental in introducing the physical ideas of quantum theory and relativity to mathematicians and informing physicists of the significance of the mathematical ideas of early twentieth century in physics. He described himself as an "unwelcome messenger" between the two communities -- reflecting the mutual disregard of the two communities that was present in the early decades of the last century.

Like many early contributors to quantum physics, Weyl fell under the spell of mystical doctrines. In his popular textbook on general relativity, Weyl writes,

the real world, and every one of its constituents with their accompanying characteristics, are, and can only be given as, intentional objects of acts of consciousness,

and he opens his 1934 Yale lectures on `Mind and Nature' claiming

the mathematical-physical mode of cognition ... is decisively determined by the fact that this world does not exist in itself ... [but] only as that met by an ego.

John Archibald Wheeler is arguably one of the most influential theoretical physicists of the second half of the twentieth century. Although he did not win a Nobel Prize, he supervised 46 PhD students at Princeton University two of whom won the prize: Richard Feynman for his contribution to quantum electrodynamics, and Kip Thorne for his role in the design and construction of the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves.

"It is not only that man is adapted to the universe. The universe is adapted to man. Imagine a universe in which one or another of the fundamental dimensionless constants of physics is altered by a few percent one way or the other. Man could never come into being in such a universe. This is the central point of the Anthropic Principle. According to this principle, a life-giving factor lies at the centre of the whole machinery and design of the world."

"It from bit symbolizes the idea that every item of the physical world has at bottom -- at a very deep bottom, in most instances -- an immaterial source and explanation; that what we call reality arises in the last analysis from the posing of yes-no questions and the registering of equipment-evoked responses; in short, that all things physical are information-theoretic in origin."

"may the universe in some strange sense be 'brought into being' by the participation of those who participate? ... 'Participator' ... strikes down the term 'observer' of classical theory, the man who stands safely behind the thick glass wall and watches what goes on without taking part. It can't be done, quantum mechanics says. ... Is this firmly established result the tiny tip of a giant iceberg? Does the universe also derive its meaning from 'participation' "?